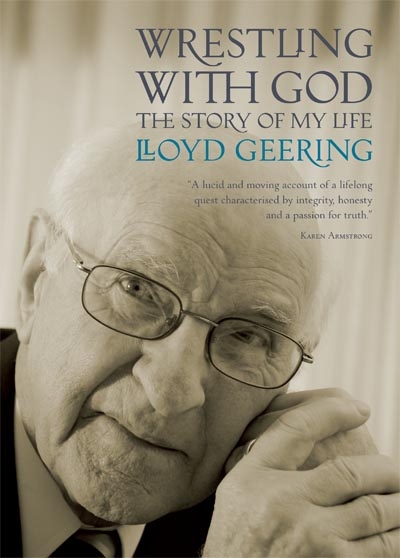

Wrestling

with God: The Story of My Life

by Lloyd Geering

To New Zealanders Prof Lloyd Geering

is our equivalent of

In 1967 when he was Professor of Old Testament

and Principal of the

Now in his late eighties he has set

down the story of his life and the progression of his theological

thinking. He says “I am my life

story, as yet still open-ended and unfinished . . .thus to find out who I am, I

must recall the story of my life as clearly and honestly as I can.” This he

does with humility and candor. I thoroughly appreciated reading his story as

told by him.

When his previous text was published

(Christianity Without God -2002) I was a respondent at a day

seminar in which the thesis of the text was presented. Then and now I find

there is much Lloyd says that I wholeheartedly agree with and much I see and

experience differently. More importantly I respect his expression of Christian

living, integrity and scholarship. I equally deplore the way he has been

vilified by many so called ‘Christians'.Â

Personally I find Lloyd's expression of an orthopraxis of Christian life

more engaging and ‘Christ-like' than the faith expressed by many of his

orthodox opponents. Such responses have only done harm to the legitimacy and

public place of Christian faith within

I find myself agreeing with much of

his theology and approach and yet disagreeing with his understanding of ‘God'

as merely a human construct.Â

As Colin Brown, previously Professor

of Religious Studies at Canterbury University and a contemporary of Lloyds,

says in his own review of Lloyd's autobiography – “Where belief is concerned,

it appears that Geering did not move from a carefully articulated, orthodox

belief in God to his present position. His adoption of Christianity during his

student days had more to do with the warmth of Christian fellowship which he

found, especially in the Student Christian Movement, the ethical challenge of

the teaching of Jesus, and his desire to give meaning and purpose to his life.

“Insofar as I thought about God at all, ‘he' was simply part of a total

package.1”

So this is not an account of someone

whose faith moves from a more orthodox conservative position towards a more

liberal perspective. Through-out his life Geering seems content to leave ‘God

as unknowable'. Although, like many, a period of grief2 (after the

death of his first wife – Nancy) led him to a hope in eternity. This he

describes as founded on the then very popular book by Frank Morrison – ‘Who

Moved the Stone?' Later he realized that although the argument of the

book was convincing Morrison had based his argument on the ‘historicity of the

gospel' accounts. Accounts Geering did not see as ‘historical' in content. A

perspective which encapsulates his theology. Not surprisingly there is no

mention of a personal sense of God or religious experiences.

There is an old Jewish saying that

an hour a day of religious reading is an hour of prayer. If this be true Prof

Geering's life is certainly steeped in prayer as his breadth and depth of

scholarship verify. However, if prayer is understood as reflection, meditation,

silence before, and communication with, God, then Prof Geering's life story is

left bereft. Nowhere is this secondary understanding of prayer discussed or

illustrated. For him luck and chance have replaced prayer and an active God:

“In this exercise of recalling

the past, I have been struck by the frequency with which I was led to

significant turning points or major achievements by chance events. Chance plays

a dominant role in the life of every person, just as it has in the evolution of

the planet – on a far grander scale! That is why we so often speak of ‘fortune'

and ‘misfortune', ‘good luck' and ‘bad luck'. As I observed at the beginning of

this book, one's genes and one's mother culture are the two ‘given's' out of

which personal identity begins to evolve. We are largely the product of these,

together with our successive responses to the many chance and intentional

events we encounter from birth onwards. [then with typical good humour he adds]

Why, I might never have become a writer had it not been for my critics!

(p248)”

At this foundational point I do not

agree with Prof. Geering. From this foundational disagreement our respective

understandings of life and faith, theological constructs and sense of hope for

our own [and the world's] present existence and future differ. And differ

markedly. Yet there remain many areas where I find myself strongly agreeing

with him. Two stand out:

The church and culture.

In the early 1970's Lloyd wrote an

article for a newspaper saying:

“there is a widening gap between

the diminishing churches and the increasingly secular community. . the church

has come to live a ghetto existence within her own confined circles, with her

own form of Yiddish, a churchy language which is quite meaningful to many of

those who have been trained

in it but deadly dull and

increasingly meaningless to each successive generation of the world outside.

We in the church would do well to

heed the dictum of Coleridge, ‘He who loves Christianity more than truth, will

soon come to love his own denomination more than Christianity and he will end

up loving himself most of all.”

Graciousness and honesty in debate

There are many vigorous theological

debates swirling today. Perhaps the most vigorous is over the inclusion of

people in same-sex relationships. Here Prof. Geering's perspective and approach

has much to teach us. He honestly pursued the truth at all cost. He listened

carefully to his critics and those who accused him of heresy. He tried to reply

to people's letters and questions openly and with concern for the person. But

most importantly he was gracious and acknowledged the place of other

perspectives than his own.

There remains much to

learn from Lloyd's theology and writing, his understanding of the church and

especially his graciousness when under attack and commitment to the pursuit of

truth.

Alan Jamieson

1 Review by Colin Brown in The Anglican Taonga;

Advent 2006. Â No.23 p50-51

2 There has been much

grief in Lloyd's life. His journey through these very sad times is an engaging

and moving aspect of his biography. “His firstborn child was stillborn, his

first wife, Nancy, died soon after the birth of their second child, a grandson

died in a cot death and Elaine, his second wife, died on the verge of

celebrations for 50 years of marriage”( Review by Colin Brown in The

Anglican Taonga; Advent 2006. No. 23 p50)